Kindergarten readiness a priority at Lincoln Park

- March 26, 2016

- / Reggie Dogan

- / early-learning,report-sci-early-education

Emily Ellis, VPK teacher at Lincoln Park Primary School, leads her pre-K class in a discussion of “Chicka Chicka Boom Boom.”

Cassandra Smith is a self-described workaholic.

That’s how she approached her life, her career and the small school she runs in Pensacola.

In her third year as principal at Lincoln Park Primary School, Smith has been at the helm of a turnaround that has made the school a beacon of light in the shadows of poverty, conflicting (and confusing) state rating systems and low funding.

Four years ago the school faced closure by the Escambia County School District because of falling attendance and failing academics. The district shuffled the fourth- and fifth-graders to other schools and brought in new leadership and staff.

With just under 200 students from preschool through third grade, Lincoln Park has risen from an F in 2013 to an A this school year, based on the state’s rating system.

Another, and no less significant achievement, was the school’s efforts to get children ready and prepared for kindergarten.

Lincoln Park was one of two schools of 14 district-led Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten programs to earn a 100 kindergarten readiness score.

“There’s been a cultural change in the school, and for me as a leader, that’s not a whole lot I have to give of myself to make this work for everybody,” Smith said. “Because we had to change the culture and climate of the school, it is important to be hands-on in the classrooms everyday to let my teachers and students see my face.”

Cassandra Smith, Lincoln Park Primary School Principal, credits her staff and students for putting in the extra work to raise the school’s grade to an A and to score a 100 kindergarten readiness rate.

Escambia schools Superintendent Malcolm Thomas said Lincoln Park clearly is a different school than it was three years ago.

In addition to new teachers and principal, the school implemented a curriculum rich in STEM (science, technology, math and science) activities, including the arts and music.

“They’re doing a great job by taking a challenging population and proving that, given the right kind of attention, they can increase aptitude,” Thomas said.

Worthwhile investment

Kindergarten is, in many ways, the gateway to a child's educational journey. While kindergarten is not mandated in Florida, the increased educational demands brought about by the tougher standards and an increased focus on school grades and state testing mean there's even greater emphasis on learning in kindergarten.

That’s all the more reason why at a school that serves a community facing societal and economic challenges, the benefits of a high-quality pre-K are immeasurable. It is critical to closing the achievement gap between children of different economic backgrounds and for preparing them for kindergarten, primary school and beyond.

The Studer Community Institute Dashboard’s kindergarten readiness metric shows that 66.2 percent of Escambia County’s 5-year-olds are ready for kindergarten.

Of the nearly 3,000 kindergartners in Escambia County Schools this year, about 1,000 of them weren’t ready for school.

More than 175,000 4-year-olds statewide participate in VPK, which is 77 percent of all eligible children.

In the first year of VPK in 2002, the state allotted $2,500 for early learning per child. More than a decade later, the allotment is $2,437 for each child in VPK, less than when it started.

Escambia County’s share of the funding for this current school year is $5.4 million.

VPK offers childcare providers funding to pay for a half-day of preschool for all Florida 4-year-olds.

That means a child would have to either leave at noon or go to day care to continue for a full day.

Lincoln Park is among 14 schools in Escambia County that receive Title I money to pay for a full day of VPK.

Most agree that a full-day VPK is a worthy investment to provide a high-quality early education for young children.

“The extended time is good because the teachers get a chance to go in-depth,” Smith said. “VPK should be for the whole day, and we are fortunate to have it.”

High-quality environment

As interest in pre-K has increased and more states have implemented pre-K programs, policymakers have identified core requirements for program success. These include: highly trained teachers with expertise in early childhood education, learning goals tied to K–12 standards, low child/staff ratios, and small class sizes.

Model pre-K programs validate the benefits of hiring teachers with a strong background in education and training. More recent state pre-K studies also document the effectiveness of programs with certified teachers with college degrees.

Having trained, certified teachers with college degrees is a crucial in providing a high-quality early education, said Marsha Nowlin, Escambia’s director of Title I.

“We have certified teachers and qualified para-professionals,” Nowlin said. “There are lots of opportunities to individualize.”

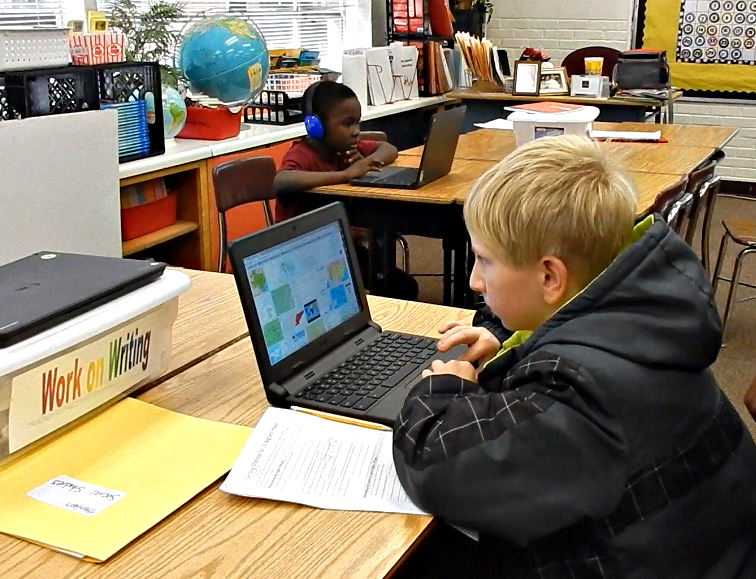

At Lincoln Park, about 40 students in two classes participate in VPK, with another 60 students in three kindergarten classes.

With a small number of classes and fewer students, Smith was able to buy iPads and Leap Frog Tag books for each student using Title I money.

A Tag book is an electronic handheld stylus that plays prerecorded audio. Children use it to learn how to read through hearing sounds.

“You can walk into any class and each person could be sitting at a table with an iPad or Tag book, playing educational games,” Smith said.

In another part of the room, the teacher could be having a small group lesson, working on numbers, letters or a STEM activity.

Laura Colo, Escambia’s Title I assistant director, spent time developing the STEM program at Lincoln Park.

Having the STEM curriculum integrated into the every aspect of the classroom is a bonus that enhances learning at all levels, Colo said.

“They use the creative curriculum, which is designed to integrate all of the learning throughout the day in math, science, literacy and reading,” said Colo. “The language and vocabulary is so important in everything we do, and it well-serves our students.”

Hiring the right people

If orange is the new black, then kindergarten is the new first grade.

Tougher academic requirements, increased pressure from state-mandated testing and higher expectations in the classrooms have more parents wondering if their children are ready for kindergarten.

There is no single indicator to determine when a child is kindergarten ready, but your child is probably ready to start kindergarten if he or she:

- Listens to instructions and then follow them. Children need these skills to function in class, to keep up with the teacher and with their peers.

- Is able to put on his coat and go the bathroom by himself. Children need to be somewhat self-sufficient by school age.

- Can recite the alphabet and count. Most kindergarten teachers assume that children have at least a rudimentary familiarity with the ABC’s and numbers, though these subjects will be covered as part of the kindergarten curriculum.

- Can hold a pencil and cut with scissors. He will need these fine motor skills to begin working on writing the alphabet and keeping up with classroom projects.

- Show interest in books. Does he try to “read” a book by telling a story based on the pictures? This is a sign that his language development is on a par with other kindergartners and that he’s ready to start learning how to read.

- Curious and receptive to learning new things. If a child’s curiosity is stronger than his fear of the unfamiliar, he will do well in school.

- Get along well with other kids. Does she share and know how to take turns? She’ll be interacting with other children all day, so your child’s social skills are particularly important for success in school.

- Work together with others as part of a group. The ability to put his needs second, to compromise and join in a consensus with other children, is also part of emotional competence.

While Smith relishes the integration of STEM in every classroom, she believes the success at Lincoln Park is mostly because of teachers she has hired and brought along with her.

That includes teachers like C.C. Lambert, with whom Smith worked at other schools and whose wife teaches third grade at Lincoln Park.

Lambert — a special-education support facilitation teacher — works with students in small groups who need extra help.

I am a workaholic who works all the time, and you have to know the people who want to follow me here have to be workaholics too,” Smith said.

With a minority enrollment of 80 percent and 82 percent of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals, Lincoln Park sits in a mostly impoverished neighborhood on Kershaw Street, near the Interstate 10/U.S. 29 interchange in Escambia County.

Smith gives credit to her teachers and staff for accepting the challenge to work in a school that serves a low-income, disadvantaged demographic.

Part of the success at Lincoln Park, Smith said, goes to finding and hiring the right people to do the best job.

Lambert said the staff has accepted a shared vision of what their leader wants to accomplish.

“If you don’t buy into the vision of the leader, or if I decide to do my own thing, it’s a crack in what we’re trying to accomplish,” Lambert said. “So having the right people is having people who share in the vision and willing to say, ‘this is what we are doing to set the culture of the school.’ ”

Emily Ellis, pre-K teacher at Lincoln Park Primary School, credits the school’s 100 readiness rate to teachers collectively collaborating, communicating and share ideas.

Smith hired Emily Ellis to teach pre-K not long after Ellis finished college at Western Michigan two years ago. She offered her a job over the telephone, sight unseen.

Smith was especially impressed with Ellis’ experience in teaching abroad in Africa and Europe, which Smith figured would bring a different and new perspective to Lincoln Park.

Ellis drove from Kalamazoo, Mich., unaware of the challenges that Lincoln Park presented.

Smith said Ellis immediately fit into the culture they had created to make Lincoln Park a high-performing school.

Not only has Ellis proved to be an effective teacher, she’s also has a knack for understanding the needs of her students.

“The first thing you have to do is to make sure their basic needs are met,” Ellis said. “You just have to make sure their loved and show them you care.”

Caring could mean having an extra Pop Tart to share with a hungry child. It could be allowing a tired child to rest until the others have finished breakfast. Or it could mean staying late for a parent conference.

‘All children can learn’

Teachers at Lincoln Park know that they can meet with Smith any time, any day. Her open-door policy extends to the classrooms. Teachers can expect to see Smith show up a classroom at any hour of the day.

On this day, the pre-kindergartens sit in a circle on a huge blue rug covered with numbers, shapes and alphabets.

During circle time, Ellis sings along with music to the tune of the book, “Chicka Chicka Boom Boom.”

She pulls a stack of mail from a basket that includes the letters of the day.

“Guess what I have in here,” Ellis said, her voice rising with inflection. “All these letters are for us.”

For children in preschool, learning has to be interactive and fun, Ellis said.

“There’s a big push away from play, but they learn so much through play,” Ellis said. “That’s how I try to run my small groups. They have self-directed play, which is center time, for an hour. They play and they learn how to play with each other.”

What makes Smith most proud is seeing the teachers working together, developing lesson plans, spending extra time with challenging students, staying late for conferences, programs and meetings with parents.

“One thing I wanted to do when I came here three years ago is to have true collaborative planning, and I can say this year it is working the way I want it to,” Smith said. “They get together in the evening and they forget what time it is. They get off at 2:45, and at 4:30 I’m sitting up there in my office and they’re still here.”

On the brink of closure in 2012-2013 school year, Lincoln Park Elementary School was restructured as a primary school. Lincoln Park Primary School earned an A raring by the state and its kindergarten scored a 100 on readiness scores.

The Lincoln Park team takes to heart the three C’s: culture, communication and collaboration.

Kindergarten teacher La’Tris Sykes said the school’s foundation is built on collaboration.

Even with nine years of teaching experience, Sykes said she’s open to learning from colleagues who may have just started.

“For me to be able to go into somebody else’s room and say, ‘This is not working for me,’ but then they are able to make it work,” Sykes said. “We learn from each other.”

One area that schools like Lincoln Park needed to improve was parental involvement.

Effective parental involvement comes when a true partnership exists between schools and families, according to the Center for Public Education.

In a CPE survey of teachers, two-thirds believed that their students would perform better if their parents were more involved in their education, while 72 of parents say children of uninvolved parents sometimes “fall through the cracks” in school.

Reaching out and engaging parents has become a hallmark of Lincoln Park’s approach to improving student achievement.

Smith’s open-door policy extends to parents and visitors. Through her office window, she can see everyone who enters. She answers her direct phone line.

Among other activities to encourage parental engagement, Smith hosts a book club, math workshop, report card conference, a family STEM night, and breakfast with books for pre-K.

“The two things I think that has helped me at Lincoln Park are parental involvement and hiring the right people,” Smith said. “You have to have the right people in place who believe what you believe, that all children can learn.”

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs