Listen to voices from

- June 1, 2016

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

So we know that words are the problem.

The groundbreaking research of Betty Hart and Todd Risley, the University of Kansas team who documented the gap in the number and kind of words that poor children hear compared to those from better-off families gave the world "the achievement gap."

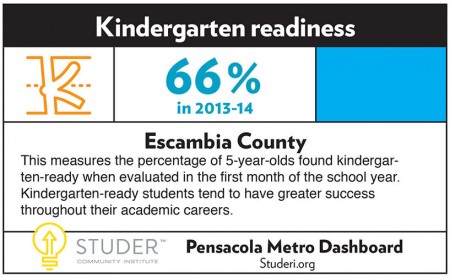

Their research found that poor children heard nearly 30 million fewer words by age 3 than children from wealthier homes. The gap impacts the kindergarten readiness of these children, a measure that the Pensacola Metro Dashboard tracks as part of gauging the quality of life in the community.

It shows that according to the most recently available data, 66 percent of kindergarteners in Escambia County were ready for school.

It also tends to lead to academic struggles throughout that child's school life, something that has been shown to lead to lower high school graduation rates, poorer job opportunities, lower wages and other lost social and economic opportunities.

But one Harvard economist wants to make sure the voices of the children who disproportionately make up that gap — young African-American boys — are heard when it comes to what would make school work better for them.

NPR featured Ron Ferguson and his latest report Aiming Higher Together: Strategizing Better Educational Outcomes for Boys and Young Men of Color. It was part of a report commissioned by the Urban Institute to review data in the field to look for strategies to help young boys of color close that gap.

Ferguson notes that all children do best when what they are able and willing to do is matched with an environment that has high expectations of them.

Building that in some communities is more challenging than others, Ferguson says in the interview. And it's something that teachers, preschool and childcare teachers, parents and education leaders all need to be aware of.

And so what we find is that when children show up in kindergarten and are already a little bit behind their peers, there are already things they aren't understanding in class. And there are times that they feel, "Maybe I don't belong here, maybe I don't really fit in here." This is especially true if, as in many schools, kids are teased for making mistakes.

Then the older kids start to teach them their identities; they start to teach each child how someone like you is supposed to behave. As kids get older, they're more and more subject to stereotypes. And adults anticipating that the young man of color is going to be defiant — the adult comes on hard, the young man anticipates this, and it leads to an escalation of misunderstanding and misbehavior and overreaction on both sides of the transaction.

Disproportionately for young men of color, you end up with out-of-school suspensions and other forces that alienate young people from their environment.

Breaking that cycle means meeting parents where they are and making sure they have the tools they need to be good first teachers.

How to do that?

Studer Community Institute research fellow Reggie Dogan recently highlighted some of the programs and nonprofits that do education-related home visits for parents. Home visits can be an effective tool for helping parents who may need help. Read Reggie's story here.

Ferguson suggests building community level networks of support around parents who need extra help to understand the importance of early cognitive development and how they can shape it.

He also notes that access to high-quality preschool is key, as would be paid parental leave policies for parents of infants.

We find that the gaps are not simply socioeconomic. Different segments of our population have different histories with regard to the way we give care and parent our kids.

Some segments of the community are very focused on lots of interaction beginning at birth. Other segments of the population never had historically the experience to prepare them to do these things.

Many of us who are people of color, as I am, have not come from generation after generation of privileged folks. We've not been in communities where there's a lot of shared knowledge of certain parent/caregiver practices, for example.

And so, as we go about this work, we need to understand that we're talking about all people. We're talking about human nature stuff. We're not only talking about extreme disadvantage or helping only the poor.

We're talking about working on lots of different dimensions — of which race and ethnicity are important — even among families where the parents are highly educated.

And that last point is important to remember.

These strategies — talking more with young children before they turn 3, building learning and reading into everyday activities, sights and sounds, tuning in to what young children are doing and doing it with them — work on all children.

They are important for every child's growing brain.

Embracing the lessons that early brain science have for how every adult can help make sure our children are ready for kindergarten, on a good path to school success and ultimately able to get jobs that will help them raise a family, pay taxes and be part of the community, is more than a feel-good mission.

It is, experts increasingly agree, a path to building economic development and a quality of life that can make our city the envy of the region.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs