Removing barriers that keep poor kids from learning

- December 22, 2015

- / Reggie Dogan

- / education

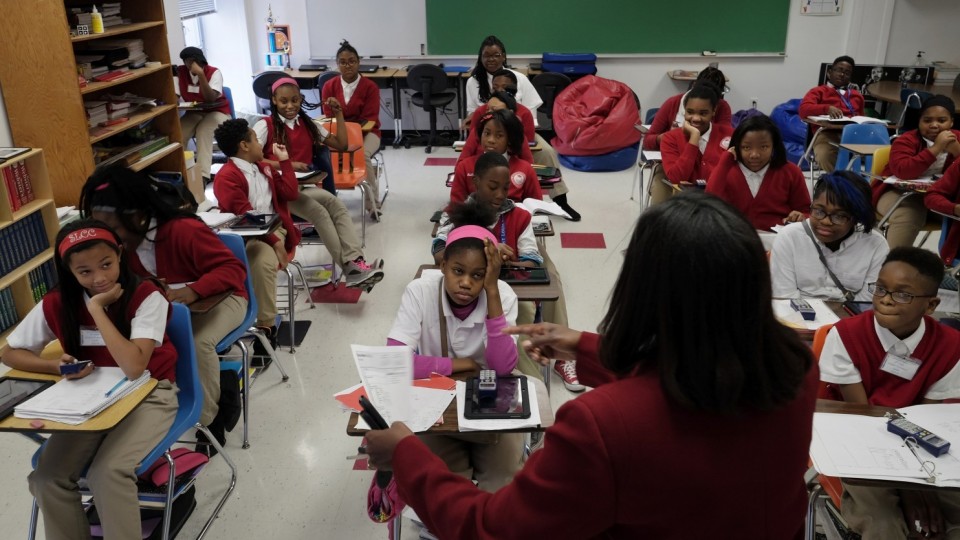

Tiffany Anderson, the superintendent of the 3,000-student Jennings School District in Jennings, Mo., addresses college-prep students on Dec. 10. Anderson has a

"hands-on" approach and visits classrooms frequently. She has brought additional funding, initiative and momentum to the district. (Bonnie Jo Mount/The Washington Post)

It’s hard to argue that poverty does not affect education. Children who come from homes where they may be wanting — wanting for food, for time or for resources — enter the school door with a little less than others.

In a recent report, the Studer Community Institute, in partnership with the University of West Florida, used U.S. Census data to map poverty among families with children in the Escambia and Santa Rosa County area.

The data found that in eight Census tracts in Escambia County, at least 1 out of every 4 children live in poverty.

In 30 of the 71 Census tracts in Escambia, at least 1 of every 10 children live in poverty — and there are 8,200 children under age 5 living in those areas.

In Santa Rosa County, only two Census tracts have a poverty rate among families with children of 10 percent or higher.

We know that 66 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-priced meals; only 66 percent of high school students graduated from high school on time in 2014 and 66 percent of children scored ready for kindergarten.

The high school graduation rate and kindergarten readiness are two of 16 benchmark metrics that the Studer Community Institute measures in the Pensacola Metro Dashboard. Developed with the University of West Florida, the dashboard is a snapshot of the educational, economic and social well-being of the community.

In the realm of education, poverty is recognized as a impediment to academic achievement and success in school. And not every school district is able to meet the challenge that poverty presents to make education meaningful and worthwhile for children suffering from socio-economically deprived lives.

But there are some exceptions, and one of them is making a big difference in the lives of its poverty-stricken students.

Jennings School District of Missouri, just north of St. Louis, was determined to remove the barriers that keep poor children from learning.

As the new superintendent three years ago, Tiffany Anderson adopted a hands-on approach that brought in additional funding, new initiatives and momentum that turned a poor district upside down.

In 2015, 92 percent of high school seniors graduated on time, and 78 percent of those graduates joined the military or enrolled in post-secondary training within six months of finishing school, according to state data.

Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon invited Anderson and a student to the state of the state address this year, praising the school district for its “big leaps forward."

In “This Superintendent has figured out how to make school work for poor kids,” Washington Post education reporter Emma Brown highlighted the positive impact Anderson has made at the school that serves mostly low-income, high-poverty students:

School districts don’t usually operate homeless shelters for their students. Nor do they often run food banks or have a system in place to provide whatever clothes kids need. Few offer regular access to pediatricians and mental health counselors, or make washers and dryers available to families desperate to get clean.

But the Jennings School District — serving about 3,000 students in a low-income, predominantly African American jurisdiction just north of St. Louis — does all of these things and more. When Superintendent Tiffany Anderson arrived here 3 1/2 years ago, she was determined to clear the barriers that so often keep poor kids from learning. And her approach has helped fuel a dramatic turnaround in Jennings, which has long been among the lowest-performing school districts in Missouri.

In Jennings, a small town of about 15,000 that borders Ferguson, Mo., one-quarter of its residents live below the federal poverty line, according to 2014 Census Bureau data. The median household income is $28,429. Only 13 of those age 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree, half of the state average, Brown reported.

But Anderson was undeterred and determined to prove that poor children can achieve and succeed in school.

Anderson’s enthusiasm and work ethic is contagious, Brown writes:

Her energy has helped persuade teachers to buy into initiatives such as Saturday school that require extra hours, said Curt Wrisberg, an elementary school principal who has worked in Jennings for more than 20 years. “If you see her doing it times a thousand, how can we not do it? She’s nonstop,” Wrisberg said.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs