The new normal in kindergarten readiness

- October 29, 2015

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

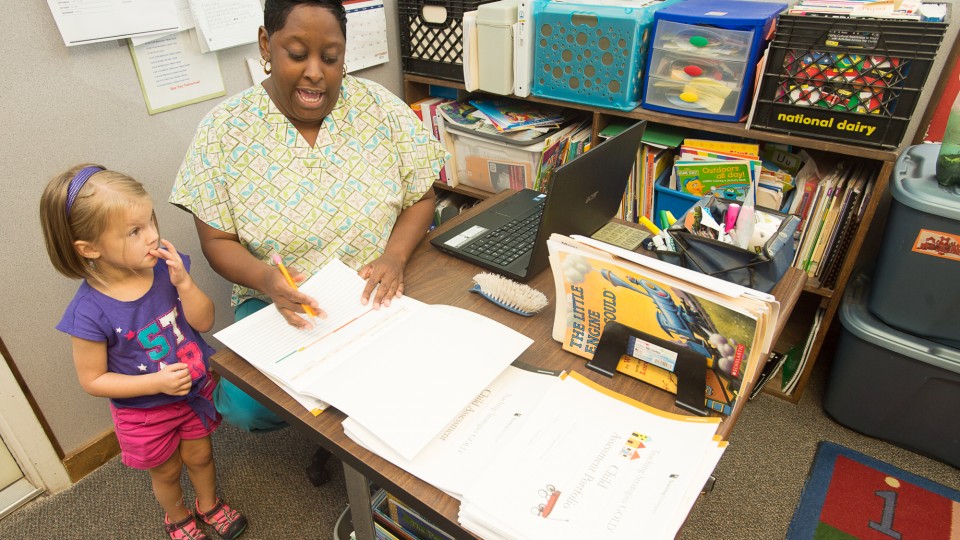

Pre-K teacher Shemetri Charley does an observation with Bella Denham at Wee Kare Academy Friday, Sept. 11, 2015. (Michael Spooneybarger/ Studer Community Institute)

Someone is always watching at Wee Kare Academy in Pensacola.

From observing while the children in centers to making notes of how they work in small groups, Brenda Hardy and her staff are always tracking how what their preschoolers are doing.

“If (Pre-K teacher Shemetri Charley) is at a table working with a group, and they are sorting, she’ll observe their conversation, make notes,” said Hardy, who is the director of Wee Kare. “It helps her get a picture of the kids, their stronger points and weaker points.”

All of those observations go into a portfolio.

Pre-K teacher Shemetri Charley goes thru her weekday plans at Wee Kare Academy Friday, Sept. 11, 2015. (Michael Spooneybarger/ Studer Community Institute)

While Hardy says building a portfolio of a child’s work has always been part of what Wee Kare has done, the level of detail now required as the state looks more closely at kindergarten readiness is adding to the workload.

It’s not the scrutiny that bothers Hardy.

“It probably takes the whole nap time, which is two hours, to record the data,” Hardy says. “You do have to write enough so that Tallahassee understands what they’re reading.”

In addition to lesson plans for the week, it adds a good five hours more to what they’re already doing a week, she says.

“If you want accuracy in the program, you’ve got to add more time to your payroll. But if you take that $15 an hour for another five hours a week, you don’t end up making any money off the program,” Hardy says. “Not that we don’t love what we do, it’s just not cost-effective for us to do it. I don’t mind doing it, but we’re not being paid enough to do it right.”

As the state demands more accountability from providers of VPK, it hasn’t offered them any more money for the added work, something that rankles.

“We may have gotten 2 cents more this year,” Hardy says.

More and more research points to the critical importance of early education in a child’s life. And yet, data from the Florida Office of Early Learning indicates that many students in the Pensacola metro area aren’t getting the benefits of the state’s free voluntary prekindergarten program meant to help prepare 4-year-olds for school.

In the 2013-2014 school year, 66 percent of Escambia kindergarteners were ready for school based on their performance on state measurements. In Santa Rosa, 81 percent were kindergarten ready.

Kindergarten readiness is one of 16 metrics in the Studer Community Institute’s metro dashboard, an at-a-glance measure of the educational, economic and social well-being of the community.

Providers learning new system

In years prior, VPK providers got their kindergarten readiness scores based on how their kids performed in evaluations done by public school kindergarten teachers in the first 60 days or so of school.

Beginning in the 2016-2017 school year, VPK readiness scores will come from tests providers themselves will administer.

It uses observation three times a school year to rate a child’s performance on a laundry list of observational behaviors at each age group.

Pre-K teacher Shemetri Charley does an assessment with Ca’Miyah Robinson at Wee Kare Academy Friday, Sept. 11, 2015. (Michael Spooneybarger/ Studer Community Institute)

It includes math and language arts milestones (counting with blocks, recognizing numbers and letters, sight word development), as well as social and emotional development milestones.

Children can be scored on a continuum — always, sometimes, not yet, never. Previous assessments were more focused on phonics and math.

This year, providers will do only one evaluation on the system — in the spring. For the 2016-2017 school year, they will test kids three times — at the beginning, middle and end of the school year.

Florida has had VPK since 2005, and has seen several changes in that time.

That includes new bureaucracy at the state level, a new ratings system, declining state funding and issues with the test to determine kindergarten readiness.

The Escambia County Early Learning Coalition administers the VPK program in the county. Executive Director Bruce Watson’s budget for VPK is $5,420,650 — $2,360 per child.

“Historically, we spend what they give us,” he said, but state funding has declined every year since 2007.

“Our lawmakers are failing to understand the impact of their decisions, when we’re paying (providers) less today than we did eight years ago and expect the same results.”

Escambia School Superintendent Malcolm Thomas believes the new evaluation system, once it is fully in place in VPKs, will give a child’s school readiness.

“I believe that’s a more efficient way to deal with kindergarten readiness,” Thomas said. “Measuring them at the beginning of kindergarten after a summer off to gauge readiness is not the best measurement.

“All kids regress to some degree in the summer,” he says.

For this school year, Thomas says his kindergarten teachers will use Discovery Education assessments to gauge the readiness of the 2,959 kindergartners in the district this year.

“We still are going to measure them when they come to school,” Thomas says.

The district’s assessment includes looking at literacy readiness, how many letters you know, how far can you count, evaluating motor skills, can you hold a pencil, can you stand on one foot and hop, where a student is in terms of milestones for typical for a 4- or 5-year-old, Thomas says.

Getting an early start

As the system rolls into use, Thomas hopes confidence in it will grow. Having readiness be measured by the VPKs should address a concern that some providers have expressed for years.

Shemetri Charley watches over her pre-K class at Wee Kare Academy in Pensacola. The Academy is nationally accredited, and its program had a readiness rate of 100 percent last year. / Photo by Michael Spooneybarger

“If the evaluation is how well they score in kindergarten, what if half of my kids went to private school?” Thomas says. “(Providers would say) you’re measuring me on 50 percent of my kids, that’s not fair.

“Testing the children at the VPK also allows them to catch an issue while they’re in the program,” Thomas says. “And hopefully it makes those teachers aware of who those kids are and you’d hope those beginning tests would drive instruction to get them better ready.”

Hardy is ready for what her center’s results will show.

“I hope it shows the state the gains we make in a year’s time,” Hardy says. “It will show the hard work that our staff does to get children to make the gains.”

Hardy also hopes it will show “what did they know when they came to us?

“If you have that parent who stays involved and will help... you can only do so much with a child in the classroom. It all can’t come from the teaching staff and the school system.

“It is a joint effort.”

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs