Warrington working to bridge gap between school, community

- September 23, 2016

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / early-learning,education,report-meeting-the-challenge

Warrington Elementary Principal Dave Schmittou, in his second year at the school, keeps his office in a converted classroom space. Credit: Shannon Nickinson.

This is the third in a series of installments on the improvement plans principals are implementing at the 11 Escambia County elementary schools that received a D or F on the Florida Standards Assessment.

At Warrington Elementary School, you have to hunt to find the principal’s office.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Learn how Weis Elementary is working to improve student learning from the earliest ages.

Learn how Holm Elementary is working to improvement achievement among its students.

Learn how Sherwood Elementary focuses on parent outreach and teacher training for school improvement.

Learn how Global Learning Academy is striving to overcome the challenges of poverty to increase proficiency.

Learn how Lincoln Park Elementary is working to strengthen relationships among staff, parents and community.

Learn how Ensley Elementary is planning to boost math and reading skills as part of the school’s improvement plan.

Learn how Oakcrest Elementary is building stronger relationships to increase student learning.

Learn how West Pensacola Elementary is helping students and teachers get resources to improve academic achievement.

Learn how Montclair Elementary is reaching out to the community and increasing parental engagement to improve student achievement.

Second-year principal David Schmittou’s office is in a classroom in the heart of the school, not in the administrative suite. He picked it by design.

“I consider myself to be a change agent, but I'm not a turnaround principal,” says Schmittou, who is in his second year at Warrington after spending eight years teaching in Michigan.

“My goal isn't to come in and blow things up and then walk off into the distance and say, ‘Look at all of the stuff that we turned around,’ and then have it resort right back. This is a school that needed a brand new culture, and needed to start thinking things through a little bit differently.

“They had gotten very comfortable and they thought that this is the best that we can do.”

Warrington is one of 11 elementary schools in Escambia County that received a D or F on the 2016 Florida Standards Assessment test. There are 480 students enrolled and the school has seven Pre-K classrooms: four are special education, three are co-located with Head Start.

A key focus for Schmittou, a father of four, ages 10 and under, this year is giving his students opportunities to learn from play, something he says many of them lacked in the critical early years.

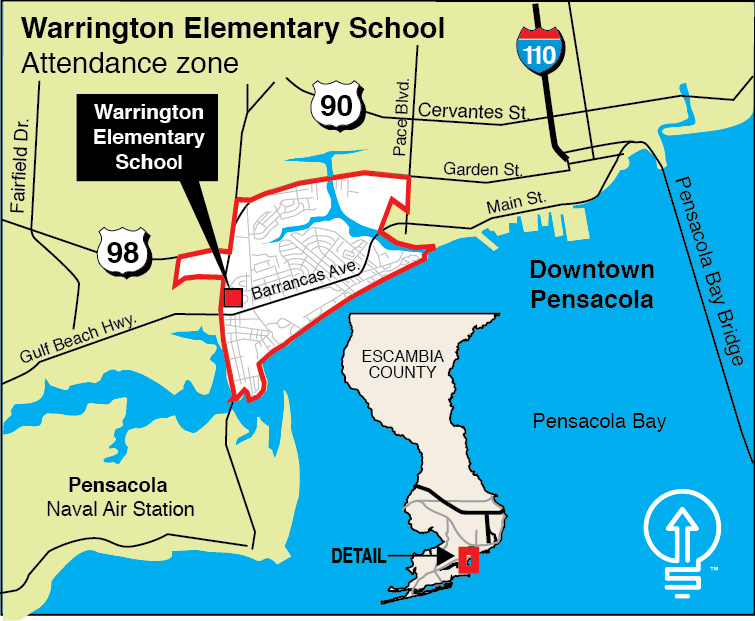

Warrington Elementary, 220 N. Navy Boulevard.

Enrollment: 480.

Teachers: 35.

Free- or reduce-price lunch rate: 100 percent.

Special education students: 18.9 percent of population.

“More learning happens from birth to 5 years old than at any other time in your life,” Schmittou says. “You can live to be 100 and you won't learn as much in those next 95 years as you did those first 5 years.

“Our kids come to school for the first time and are put in front of peers and other people they've never seen before, with no idea how to play, how to socialize, how to get along.”

Only about 25 percent of Warrington’s kindergartners were in a VPK program. For many, their early playtime was limited because where they live, it is not safe to go outside and play.

At the school, the play equipment is limited to a couple of sets of climbing bars and recycled tires.

“We don’t have a playground here, so we invent things to play with and on,” says Schmittou, whose school got a $10,000 grant to pay for indoor physical education equipment he describes as “Legos on steroids.”

At lunchtime, kids can use it to learn how to play, build, design, do all the make-believe stuff that other kids in neighborhoods with more resources grew up doing in their early years.

“Right, wrong, or indifferent, that is our huge focus, teaching kids how to play,” Schmittou says. “When you can teach them how to play, that's where learning can happen.”

Among the strategies at Warrington for this school year:

— Build a new culture. Schmittou says that 90 percent of his job is hiring the right team and keeping them challenged. There are 13 new teachers on a staff of 35 this year.

The staff who did return from last year are in it, “heart, soul, you name it,” Schmittou says. “They're the ones who have given up their entire summer, realizing things have to change.”

He recalls author Todd Whitaker in creating a culture where “we don't have a lot of crutches for people, and we don't have a lot of people carrying the burdens for everybody else. If you want to do the job here, we're going to give you the skills to do (it). If you realize that you don't have the skills, and you're not willing to get trained, we will find people … who want to do the job.”

Schmittou says his recruiting of teachers has included people from as far away as Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan and California.

“I'll be very honest, very real. I am not trying to hire a lot of people from Escambia County. I'm not looking to get a bunch of people to transfer over from other schools,” Schmittou says. “This year we have teachers ... who have 20 to 25 years of experience who wanted to come be a part of this new culture and phenomenon.”

A reading coach and a behavior coach are on hand to help make sure teachers are comfortable with the reading intervention program and to offer help for classroom management.

That includes creating a social contract in classrooms to set the ground rules for how everyone — children and adults — will act, speak to each other and address conflicts.

— Reading intervention for all. Warrington is an extended-day school, meaning students get an extra hour of instruction. Rather than viewing it as a punishment, Schmittou wants his staff to view it as an opportunity to do more for their students.

“There are a lot of people who say, ‘I can't believe I have to be there for another hour,’ ” he says. “Well, no, you get to be here for another hour, it's your day. Let's make it happen.”

Teachers will use Scholastic Reassessment, a reading and literacy program as an intervention for struggling students.

“In our building, when we have so few of our kids that are meeting those basic benchmarks, if that intervention is good for one, it's good for all. All kids get that 45-minute block of (strategic reading intervention).”

— Making connections. The school draws its students predominantly from three apartment complexes: Moreno Court, the Pines, and Warrington Village.

Last spring, Schmittou and some of the staff went to those apartment complexes to go door-to-door to reach out parents and make a connection with them.

At one complex, the apartment manager told the group they’d have to leave, because a middle-aged white guy with a badge going door-to-door was making people nervous.

This spring, Schmittou says the same person came to the school, asking if they were planning to come to the complex to get out the word about back-to-school. What changed? He’s not sure.

He does know that connecting the dots for his students to the wider world is a way to help broaden their minds and make it easier for them to build new learning concepts.

“They don't leave their neighborhoods, they don't leave their house, and they don't know what the world is like,” Schmittou says. “When we give them a reading passage to read, they're not able to make those connections.

“I was shocked that we're two miles from the (Pensacola Naval Air Station), and we have some kids who have never seen the Blue Angels, have never seen the beach and all of those sorts of things. We're asking our kids to now read and comprehend things that they can't even get a mental picture of.”

— Bringing in parents. The image Schmittou says people have of Warrington Elementary parents: “That they don’t care and they never will.”

When there is an event at the school that the kids have talked up at home, “you can’t park on Navy Boulevard. Our parents will come. They want to celebrate their kids.”

One of the things Schmittou wants to do is undo the strongholds of the way people perceive his parents.

“When I'm talking about our perception of our parents, it's the people who have been in this building for a long time and what they perceive the parent's role to be.”

He refers to his time as a middle school teacher, when the perception schools give parents is, “We’ve got this, you’re not welcome anymore.”

“In this building in particular, we have sent that message: ‘You send them to us, we got this.’ We need to change that. We need to make sure that we are reaching out to parents saying how do we help you and it's not always us saying here's how you can help us more.”

The school’s PTA had no parent members because the perception was that the PTA was for fundraising. Schmittou says his parents, for the most part, are giving all they can afford to give.

That’s kept parents at arm’s length.

Schmittou will continue family movie nights, game nights, carnivals, Donuts with Dad and Muffins with Mom, “all of the things everybody has always done, we do it but it's up to the kids to go ask their parents to come. And we can't keep them out; it's crazy. Last year we used those events to simply prove to our staff that our parents do care.

“Our parents will come support their kids. They don't want to be preached at. We're not here to tell them how to do their job differently, we just need to make it a partnership.”

— Bringing in the community. “This community, if you ask for it, they rise to the challenge.”

He cites a group that hosted a party at a local lodge where the price of admission was school supplies. They got enough to make sure every Warrington student had what they needed to start the year.

Warrington Elementary Principal Dave Schmittou, in his second year at the school, keeps his office in a converted classroom space. Credit: Shannon Nickinson.

A local Elks Lodge hosted a “teacher store” to help teachers shopping for classroom supplies. A local Methodist Church brought teachers breakfast on the first day of school. A fitness club owner does Saturday boot camps on the school’s front lawn, with all the donations from that class going to the school.

“This is a community that embraces the school,” Schmittou says. “If we can just change the perceptions outside this community …”

— Focusing on growth. Schmittou says he brought the ELEOT (Effective Learning Environments Observation Tool) system with him from Michigan.

It uses observation and data to aggregate learning outcomes based on seven focus areas: equitable learning, high expectations, supportive learning, active learning, progress monitoring and feedback, well-managed learning and digital learning.

“We have multiple measures,” Schmittou says. “Obviously, there are the FSA scores and the school grades and all of that. I may be the only administrator that you talk to about this who will say our F was deserved, our F was earned, our F is accurate.

“I will stake my job and reputation on the fact that next year we are a C or better because when I look at our data, a couple of things that we're fixing this year, if those things had been remedied at the beginning of last year, we would have been a B this year, just from those few things.”

Warrington Elementary students visit Fire Station 16. The field trip helps build bridges between the school and the community. Credit: Escambia School District and Debra Lawrence.

Warrington also will use a tool from the Oregon-based Northwest Evaluation Assessment called Measures of Academic Progress (MAP), which Schmittou says focuses on student growth more than on student achievement.

“We're not just saying did our kids pass or fail something and then teachers do not know what to do with that information, which is what we struggled with in the past,” he says.

“If we just focused on growth, our school grade would go up,” he says. “We could have not a single kid be proficient next year, not a one, and if we showed the growth that we can achieve as a school, we would be a B school next year even without a single kid being proficient or passing test.”

Schmittou says Warrington will turn its challenge into an opportunity.

“Our kids come to us so far below that norm, their ability to grow far surpasses some of the other buildings,” he says. “We just need to get our teachers to focus on growth. Don't worry about where they come to you, think about where you're going to take them.”

Schmittou says he told Superintendent Malcolm Thomas last year “it's our job here to increase the graduation rate. If we're holding kids back in first grade and third grade, that means we have overage 16-year-olds who are going to drop out and it's our responsibility.”

Three third-graders and no first-graders were retained at Warrington last year.

“My job is not to make successful fourth-graders or to make successful third-graders,” he says. “We are trying to change lives. We get the biggest bang for our buck changing lives if we get kids to finish school, which opens up more opportunities for them.”

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs