What's behind the Pockets of Poverty data?

- December 9, 2015

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

Darin Redick and his Take Stock In Children mentor Jim Smith. Shannon Nickinson/Studer Community Institute.

Data don’t lie — but they aren’t always the whole picture.

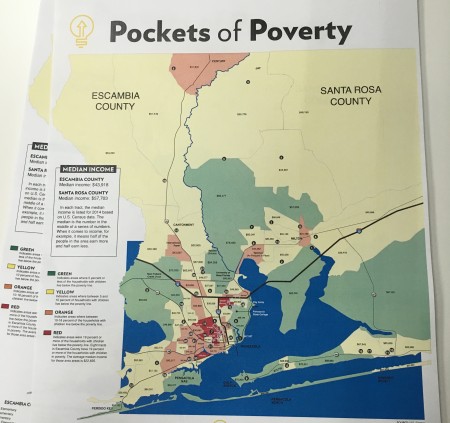

After weeks of working with University of West Florida researchers to collect and analyze Census tract data that was the basis of the Studer Community Institute’s “Pockets of Poverty” report, the numbers paint a grim picture of the depth and breadth of poverty in the Pensacola metro area.

— In about one-third of the Census tracts in Escambia County, more than 10 percent of the families with children live in poverty.

— In general, children from those neighborhoods come to school less prepared for the academic demands that are now placed on them at the kindergarten level.

— Those neighborhoods with higher poverty rates are served by elementary and middle schools that earned lower grades on state standardized tests that then more well-off peer neighborhoods.

It would be easy to think of Darin Redick as a statistic.

Redick is a junior at Pensacola High School. He went to Warrington Middle School.

He is the oldest of four children and helps his working single mother care for his siblings, who range in age from 8 to 2.

You can look at the Studer Community Institute’s “Pockets of Poverty” map and think you know a lot about Darin Redick. And what his future is likely to be.

But before you do, I wish you could meet him.

I wish you could hear him talk about how he struggled his freshman year with his advanced level classes.

The workload from middle school to high school increased — a lot. It wasn’t something Darin was prepared for.

“I was put in advanced classes,” Redick says. “I guess I just wasn't prepared for all the work and everything I was supposed to have, so I just started slacking a little bit. It was so much for me to do.”

His grades started slipping, and that’s where his Take Stock in Children mentor Jim Smith fills in a bit of the story.

Some of Darin’s classes required him to use the internet for homework, which Darin’s home doesn’t have.

His mother works and his only ride home after school is the bus, which made staying after school to get the work done not feasible.

Because he is a good brother and son, he helped look after his younger siblings, ages 8, 5 and 2. but doing that meant he wasn’t setting aside enough time to manage the assignments in his new, heavier workload.

Smith and success coach Jeanne Kimbrel worked out a solution for Darin so that he could get a ride home after school.

Smith says he also spoke to Darin’s teachers to let them know that Darin was part of Take Stock, a state program that offers at-risk students a college scholarship if they meet the program’s eligibility requirements, keep their grade point average up, stay out of trouble and meet weekly with a mentor from the program.

For Darin, that is Smith.

He says he wanted them to know that if they could let him know if Darin’s grades start to slip early on, he could help.

And he did. After a lot of hard work, Darin has been on the A/B honor roll ever since. He’s beginning to plan for college, something that he and his mom never considered possible before they found out about the Take Stock program.

But if he hadn’t had Smith advocating for him, he could easily have slipped through the cracks.

Not because he comes from a culture of low expectations.

Not because he doesn’t understand the importance of doing homework.

Not because of who is mother is or how many siblings he has or where he lives.

Because there is more to Darin than data and demographics.

Reaching kids like Darin is critical to giving him a chance to have a better life — and to this community’s chances of creating a better place to live. It is the very basis of the social contract that a public education system is meant to fulfill.

You might even say it is a moral imperative.

But if you aren’t moved by that argument, see if this moves you.

An Auburn University professor researched what increasing the state graduation rate to 90 percent would mean for Alabama’s economy. Meeting that goal by 2020 would increase the state’s economic output by $430 million.

Each subsequent graduating class that met the 90 graduation rate benchmark would add 1,200 jobs to the economy.

Are those numbers you can live with?

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs