How Santa Rosa boosts at-risk students chances to graduate

- December 17, 2015

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

The number of college graduates in a community can boost its economic bottom line.

The data is important — but the face behind it is even more so.

Especially when that face belongs to a teenager who is behind in school and at risk of not graduating on time.

That’s the sweet spot where Santa Rosa school officials have been operating for the last five years when it comes to high school graduation.

The melding of cold, hard data and the incomparable value of the human touch is key to the district’s success, particularly helping kids who are at risk of not graduating on time make it to a diploma.

From 2010 to 2014, Santa Rosa graduation rate among students who are “at risk” rose from 45.8 percent to 55.7 percent.

While the number of at-risk kids in Escambia schools is declining, the graduation rate among them has remained essentially flat for five years at 34 percent.

The Florida Department of Education says a child is “at risk” of not graduating if he or she scores a 2 or lower (on a scale of 1-5) on the eighth grade FCAT in reading and math.

In Santa Rosa County back in 2010, 274 seniors were at-risk of not graduating; 45.8 percent of them graduated.

Among the senior class of 2014, there 146 at-risk students; 55.7 percent of them graduated.

Data show not only were there fewer students who fell into the “at-risk”category, more of those who did were able to graduate on time.

Among the seniors in Escambia high schools in 2010, there were 951 kids who fit that criteria. That year, 34.4 percent of them graduated — 327 students.

Among the seniors in 2014, there were 636 seniors considered “at-risk”; 34 percent of them graduated — 216 students.

“Initially you try to make sure you have all their academic needs met, but what we settled into is a system where we find out what the student needs,” says Bill Emerson, assistant superintendent for curriculum, instruction and assessment. “You spend a lot of time talking about what they need, but not necessarily what they need to pass their algebra test.

“They could need the power turned on. They could need a Coke. They could need someone to help them get the money to pay for them to take the ACT. Or they could need a football shirt.”

Santa Rosa has for about five years now used intensive data analysis to predict which kids are at risk for failing to graduate — everything from standardized test scores over the years, to recent classroom grades to attendance.

Then they have taken that data and taken the time to learn about the child behind it.

The best example of how that has worked in the field is Milton High School, which went from a D in 2009 to a A in 2010 on state standardized tests.

The effort began under Principal Mike Thorpe and continues now under Tim Short, who is in his first full year at the helm of the school, where about half of the student body is eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

The high school graduation rate is one of 16 benchmark metrics that the Studer Community Institute measures in the Pensacola Metro Dashboard. Developed with the University of West Florida, the dashboard is a snapshot of the educational, economic and social well-being of the community.

High school graduation is widely valued because it usually leads to higher earnings for individuals, and also because studies show that communities with more-educated citizens have greater productivity and economic growth.

There is evidence that graduating high school provides an additional boost to earnings above and beyond the earnings of individuals with the same number of years of schooling but no diploma.

It goes back to the old saying, whatever you shine the light on gets attention, Emerson says.

“We’ve been trying to shine the light on these potential dropouts by making them take more school, extra sessions, summer sessions,” Emerson says. “Those are not bad intentions, but it turns out that may not have been the most important thing.”

Getting kids the help they need

The strategy is effective at Milton High, but that’s not the only school where it is used, Emerson says.

That use of data to flag kids are falling behind is part of the district’s multi-tiered system of support.

Each school in the entire district has an MTSS team — a group that includes administrators, counselors, sometimes a school psychologist — who look at what the data shows about a school’s population.

Generally, Emerson says, students fall into three tiers. Tier 1 kids are the core population who go through without many problems. “That’s where you want about 80 percent of your kids to fall,” Emerson says.

Tier 2 students may need some interventions to get on course, anything from remedial classes, or behavior modification strategies and they get back on track. Tier 3 kids, Emerson says, need more intensive interventions; some may ultimately end up in adult high school or on a GED track.

“We don’t want to do it that way,” Emerson says, “and we continue to follow up with that student because the goal is a diploma.”

That’s an important goal especially in light of the earning power that comes with that diploma.

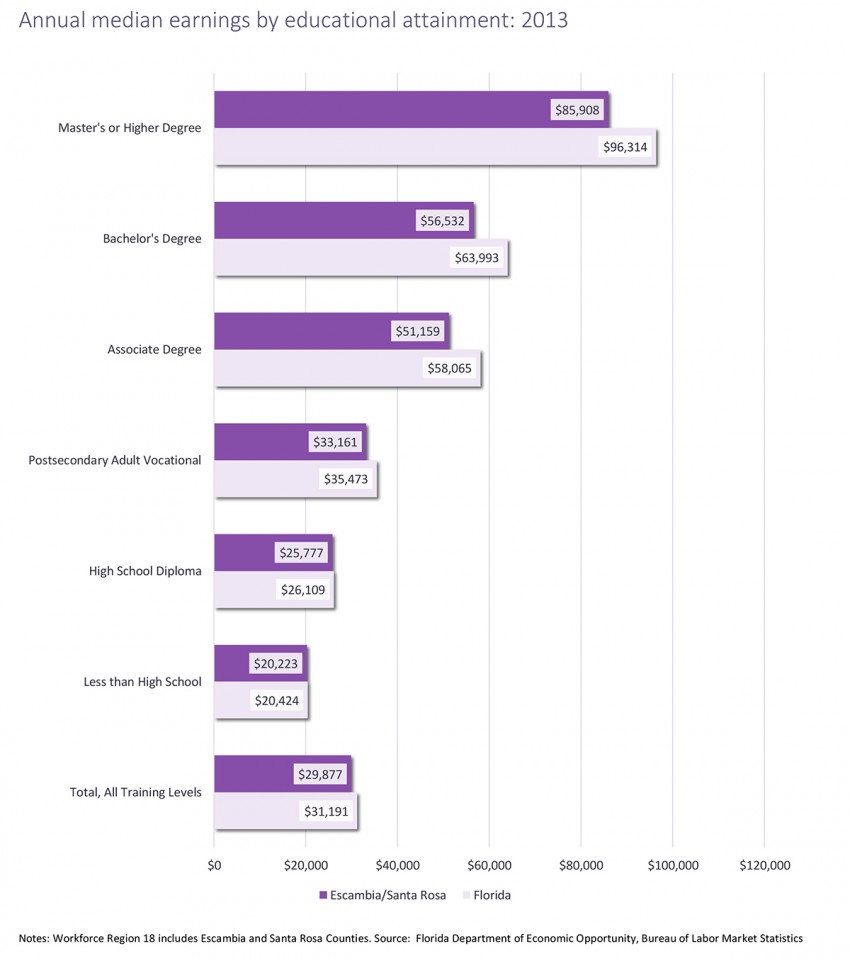

Data shows that high school graduates earn about $25,000 a year in the Pensacola metro area. Getting a vocational degree bumps that up to about $33,000; an associate’s degree bumps it up to $51,000.

A four-year college degree means a salary of about $56,000 according to data from the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity.

Annual median earnings by education attainment for 2013 according to data from the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity.

The district director of continuous improvement also meets with the MTSS team at every school at least twice a year to find out what trends there are and what is being done to address the red flags that come up.

“It’s not a gotcha kind of situation,” Emerson says. “It’s an accountability that says we’re going to check on you formally twice a year to find out where you are with your students and if they’re making progress.

“That’s the philosophy of what’s going in high school,” Emerson says.

It is a philosophy that is paying off, not only at Milton High but also across the district.

It is also connects an educator back to the thing that made them want to become a teacher in the first place — the impact that an engaged teacher can have on the course of one child’s life.

“Sometimes just the fact that you are taking the time to talk to kids rather than just showing them where they are deficient, you’ll see them re-engage,” Emerson says. “It’s paying attention to what is going on with that student and cheering for em a little bit.”

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs