Reclaiming Bayou Chico from its legacy of disregard

- December 10, 2014

- / William Rabb

- / training-development

Until the 1990s, the history of Bayou Chico was one of almost complete disregard for the environment.

It also linked closely to the economic history of Northwest Florida.

Early explorers gave the bayou the Spanish name for 'boy,' presumably in contrast to the larger Bayou Grande to the southwest. By the middle of the 20th Century, the boy was a sick old man, suffering from years of abuse and neglect.

[sidebar]

The Department of Environment Protection on Thursday is meeting with stakeholders in Escambia County to provide updates on the ongoing restoration plan for Bayou Chico.

The Bayou Chico Restoration Plan Annual Update meeting starts at 1:30 p.m. at the Escambia County Board of Commissioners Central Office Complex, 3363 W. Park Place on Palafox Street.

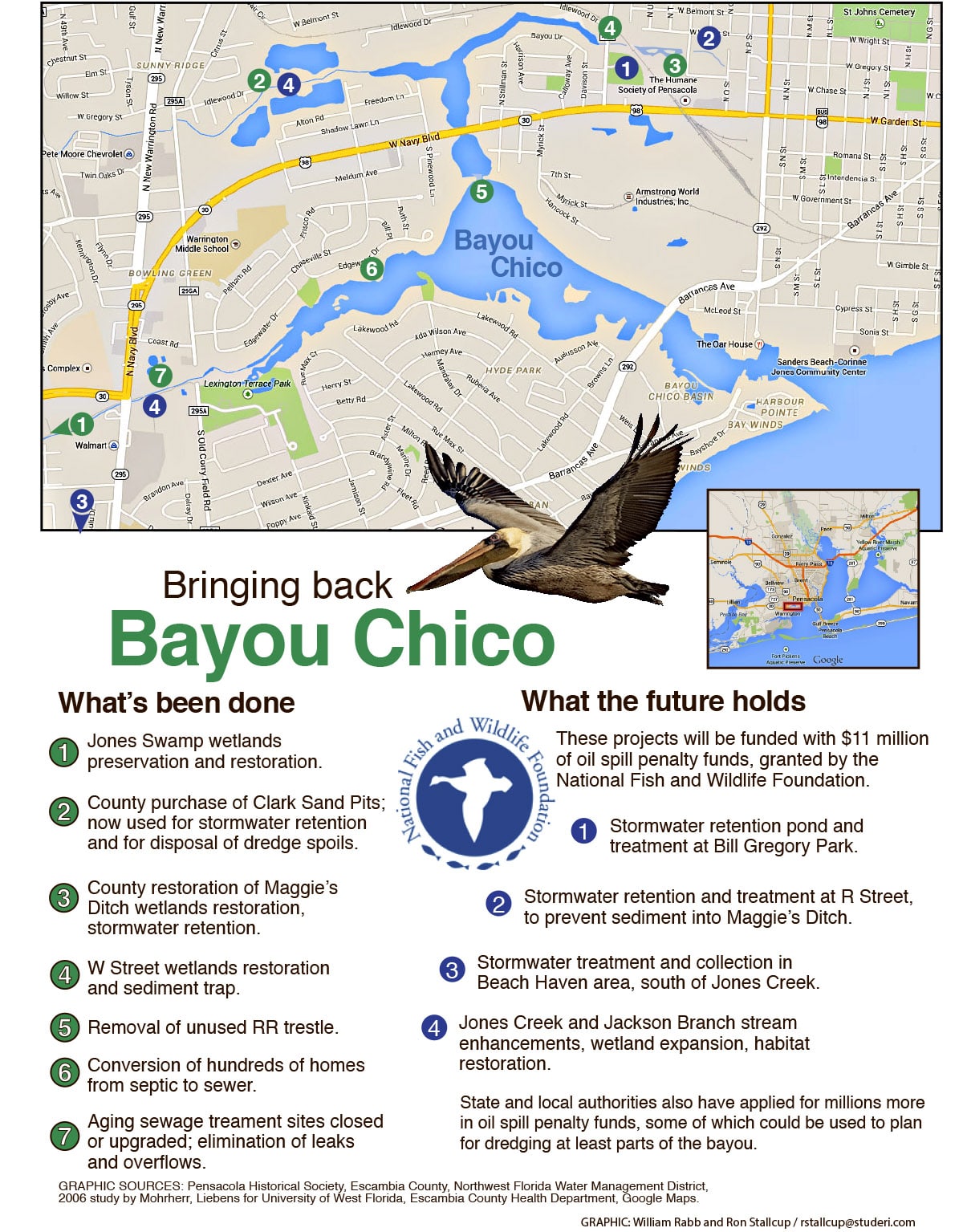

The restoration plan, known as a basin management action plan, or BMAP, covers Bayou Chico and six water body segments, all of which flow into Bayou Chico and the bay: Jones Creek, Jackson Creek, Bayou Chico Drain, Bayou Chico Beach, Bayou Chico proper and Sanders Beach.

For details about the plan, click here.

[/sidebar]

In the early 1900s, the timber industry of the Panhandle was reaching its peak. By the 1930s, the north shore of the bayou was home to nine lumber mills, three fertilizer factories, four oil terminals and four naval-stores yards (mostly storing products made from pine sap), and one beer brewery, shows a report from the Corps of Engineers.

After much of the majestic longleaf pines in the region had been cut down, Newport Industries found a way to use the stumps to extract more sap for turpentine, resin, tar and other products. The company transported the stumps to its operation near the banks of Bayou Chico, near where the Reichhold Inc. chemical operation stands today.

Newport pumped its waste product, said to resemble asphalt, directly into the bayou. Much of it is still there today, studies suggest.

Other pine-extraction and chemical companies set up shop nearby, according to historical and business records, and continued discharging untreated waste onto the ground and into the water.

In the 1950s, wood chips overflowing from Newport's holding ponds were so laden with solvents that they would sometimes spontaneously burst into flames, according to testimony in a 1995 federal lawsuit about cleanup of the site.

A 1955 study by a University of Miami researcher found that the industrial discharge into the bayou sucked the life from the waterway because it had an oxygen demand equivalent to the raw sewage of a city of 100,000 people.

In the 1950s, Pensacola attorney Grover Robinson Jr. filed a lawsuit on behalf of bayou homeowners, which forced two companies to stop discharging waste into the waterway. But within a few years, at least one was right back at it, according to Ratchford and a historical account of the bayou found at the Pensacola Historical Society's archives.

Not everyone was bothered by the pollution legacy. In 1962, the president of the Weis-Fricker Mahogany Co. wrote a public letter decrying efforts at cleaning up the bayou, because the polluted water for years had kept the dreaded toredo worms out of his mahogany logs, which were transported from Central America and stored in a lagoon at the mill on the south shore of the bayou.

In 1984, Reichhold signed a consent order with Florida environmental regulators to remediate groundwater contamination and stormwater runoff from the site, and the company took major steps to comply, according the federal lawsuit.

But the Florida Department of Environment Protection said the bayou was still “frighteningly polluted,” and considered it the “No. 1 stressed body of water in all of the Panhandle,” according to state records.

Just to the east, Pensacola Creosote, later renamed American Creosote Works, opened a wood-treating site north of Sanders Beach in 1902. It filed for bankruptcy in 1981, after decades of dumping chemical waste in unlined holding ponds.

In 1983, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared the creosote works a Superfund site. Since then, millions of dollars have been spent cleaning the soil, but much work remains. The EPA told PensacolaToday.com this week that after years of inactivity, the agency is now nearing completion of a final cleanup plan.

Project manager Peter Thorpe said the plan would be released next spring, followed by public meetings. Work involving building a slurry wall around creosote waste found deep underground, and pumping out contaminated groundwater, could begin as soon as 18 months from now – if Congress continues to fully fund the Superfund program, he said.

The cost is expected to top $35 million.

About the time that the creosote yard was declared a Superfund site, homeowners on the west side of Bayou Chico asked attorney Tom Ratchford to consider filing a lawsuit against polluters, in an effort to clean up the smelly, contaminated sediment and the yellow, waxy substance often seen on the water's surface.

Part of the homeowners' complaint was that they were being taxed at higher waterfront property rates, but they couldn't enjoy the contaminated water, Ratchford said.

His research showed that the bayou was so polluted that it rivaled some of the most infamous U.S. sites marred by industrial pollution, including Love Canal in New York and Times Beach in Missouri.

“What I explained to the homeowners is that to get this done, we had to get the public behind us, nationally,” he said. “And to do that, we had to show that it was as bad as Love Canal.”

At that, most of the homeowners balked, fearing the publicity would hurt their property values, making it impossible to sell their homes at a fair price. The lawsuit was never filed.

Ratchford said he turned his files over to then-state Sen. W.D. Childers, in hopes of seeing some state action or funding for a bayou cleanup. He never saw the files again and heard nothing more from Childers.

Today, after years of news reports and efforts to clean the waterway, Bayou Chico homeowners don't worry so much about property values, said Bayou Chico Association President John Naybor.

“People understand now that if we get it cleaned up, then property values will go up,” Naybor said.

Graphic sources: Pensacola Historical Society, Escambia County, Northwest Florida Water Management District, 2006 study by Mohrherr, Liebens for University of West Florida, Escambia County Health Department, Google Maps.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs